In this episode of Urbcast, I will be talking with Robert Martin, who is anarchitect, industrial PhD fellow, and head of mobility at JAJA Architects. With Robert, I will continue the vast topic of mobility that I started with Sofia and go even more into the details of it, talking about for ex.: the backcasting and prototyping method and the projects that Robert does together with the mobility team at JAJA Architects.

Marcin Żebrowski: Hello, Robert, thank you for taking part in this podcast. Thank you for coming here or maybe I should say thank you for inviting me.

Robert Martin : No worries, Marcin. Thanks for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

I’m really curious about the mobility projects that you are carrying out right now. I would like you to give an introduction about yourself to the listeners.

My name is Robert. I’m an architect and I’m also the Head of Mobility at JAJA Architects. We’re a small architecture and urban design firm based here in Copenhagen, Denmark.

How did you and JAJA Architects get your interest in mobility?

Well, I wish I could say that I came up with it myself, but it was driven by the partners here at JAJA. For them, it started with a parking house project that we have here in Copenhagen. It’s called “Konditaget Lüders”. I’m not sure if you know it, but it’s the giant red parking house in Nordhavn.

Yes, I know, this building. I will not repeat the name. It is too hard. But yes.

For those of you that don’t know it, it’s quite well known here, because it’s not your typical parking house. It’s this bright red parking house with an amazing public space on the top. That public space is six stories up in the air, which gives an amazing view over Copenhagen. The building itself has become quite iconic, it’s posted all over Instagram with a lot of influencers choosing to do photoshoots there. But really, what it did for us at JAJA was to highlight the relationship between transport, architecture, and the way we build cities. Because a parking house would otherwise be an infrastructure, which is dead in the city. But by rethinking it, we were able to give quite a lot back to the residents of the city. This is what started our interest in mobility.

I’ve been even referring to your project yesterday because of what you did with this parking structure and placing this public space on the top, I think it’s very inspiring. This parking gets another life and people start having an aim into just getting there because there’s this public playground – public space, which has also a very nice panorama view. I think that this is changing the perception of parking. Was that the start that you wanted to change the perception of a place?

I think it was more how much emphasis we put on the space that we give cars in cities. The parking house was our first step, the first inquiry that we had, but what launched the mobility department at JAJA was a general frustration with the way that we were forced to work in our master planning projects. At JAJA, we do a lot of master planning projects, but no matter how hard we tried to introduce more sustainable ways of moving within those projects, we were always overruled by transport engineers. Whenever we would propose to limit car-use, they would laugh at us and say: “you know, you can’t possibly have that little parking or expect that street to be that narrow, these are the traffic standards that you need to design with”. And those standards are just overly generous to cars. So we weren’t able to fight them either, we were limited in our ability to design more sustainable urban developments because we didn’t have enough knowledge on transport. So by launching the mobility department, it was a way for us to engage with transport engineers to see if we could push the envelope a little bit to try and change those standards , which are fundamentally based on modernist planning principles from 60 years ago.

So to summarize: you realized that mobility is a very important part of a project when you are planning a city or a district and you started thinking about mobility. Does mobility come first, or it’s just one of many layers?

I mean, it’s hard for me to say because I’m so into mobility right now. me, I think mobility is one of the fundamental parts of city-making. It’s the way we move around the city and how we experience it. There’s also a relationship between urban form and the way we move. To give an example, we have the historic inner core that you see in many European cities, which developed in a time when we couldn’t move that much, so proximity was the key. Then with the mass adoption of cars, we can see a process of suburbanization, which is leading to extreme sprawl around all cities, and then also the modernist housing districts that you see as well.

Many cities, including Copenhagen, where we are right now, could have looked completely different nowadays, right?

The thing is, we’re in a transport paradigm shift, where you can already see in some of the new housing developments here in Copenhagen, where the residents are being pushed towards much more of a lifestyle of cycling. This can be seen in urban developments like Nordhavn, where there isn’t, say, on-street parking anymore, and there’s a certain level of density as well as amenities that allow people to live within that area without car use. So there is hope, in some sense.

I’ve been referring to Copenhagen because I think it will be a big part of our talk, we will be talking about the examples from Copenhagen as well. But before that, I would like to ask you about your work and experience abroad, because you’ve been studying or working both in Australia, in Sydney, or the US, but also Saudi Arabia. I guess it was way different, so I wanted to ask you, how did it influence you?

I think it’s funny because it’s only Copenhagen and the US, where I have been so aware of mobility because I have lived in those countries since I’ve started working in the mobility space, whereas while I lived in Saudi Arabia and Australia it was a much more internal experience. It’s only upon reflecting on it now that I understand the influence. For instance, I grew up in Australia, in a fringe part of Sydney. I wouldn’t say it’s the city, but I wouldn’t quite say it’s the countryside, it’s a transitional area. Public transport is fairly rare in that area, so as soon as one turns 16 they’re forced to get a car because there aren’t that many other options to get around. But when I moved to Sydney for university I sold my car within six months because I found it so frustrating to get around in constant traffic, always battling to find parking, and I much more enjoyed getting around by bike. So I sold the car because of my urban environment without even thinking about it.

Living in the US for some time (I was in New Haven, Connecticut) with this whole awareness of the relationship between mobility and city-making I felt a little sorry for the residents there because even though they were living in a city centre they were tied to their cars.There was no other option after getting around in the city apart from that. And you could just tell that so much of their life was tied within their car because of the way the city had been designed.

Yes, and I can just relate – it happens everywhere. When I was growing up, back in Poland, it was the same for me. As soon as I turned 18, I got the driving license and I got the first car – an old car because that was like a natural path for many of us. And that’s why I think that our talk is very important because we can have some examples from our lives. But when you think about it, it applies everywhere. So I think that this is very important that we start to talk about mobility in general and maybe start having some projects that will show how it can be changed. And I hope that one of those projects could be your research and projects that you are making. And here I would like to start to talk about your working methodology. And the idea of backcasting and prototyping; Can you introduce this concept?

Yeah, sure. I think before I go into our methodology, I might just give a little bit of background about why we’ve developed it. As part of the mobility department, we’ve been trying to develop ways of working with traditional transport planners because we don’t try and pretend that we can do their job. They have certain tools that are beneficial to the way we plan cities, think that with our expertise as spatial designers, we can add an extra element. Transport planners, they’re discussing the efficiency of roads, or its capacity or how long a queue time is, but they’re not so concerned with for example.: is this street too wide for people to be able to have an enjoyable life?

When design meets engineering…

Yeah, exactly and that’s where we see that our work comes in now. Our methodology that you’ve asked me to explain, this idea of backcasting and forecasting, it’s split into two parallel tracks. So that backcasting is a concept that is the opposite of forecasting, which is one of the main tools that a lot of those working in engineering disciplines use, which takes historical data and trends and projects into the future, to try and guess what is going to happen. Well, backcasting does the opposite. Rather than trying to guess what the future will be, it’s about asking what we want for that future. And then finding the steps backwards, to get there. Prototyping, on the other hand, balances this. So what we do with prototyping is that we take that idea of the future, that vision that we created through backcasting, and then you sample it in the present. So you take that idea and bring it into now. And by doing that, you can gain knowledge and use the feedback to understand what that means for people? How would it work in principle? Then that can inform the backcasting vision as well. So they’re working on opposite ends as well as informing each other.

Was this something that you use for a couple of projects in Copenhagen? Can you tell us more about how you implement it? And what is your vision for car-free Copenhagen as well?

Yeah, I guess the methodology doesn’t make a lot of sense until we see it in practice. I’ll give you an example of the way we work with backcasting. So one of our main research projects has been about developing a future vision for Copenhagen in which we’re not relying on car use. It’s not set at any point in the future, because we don’t know when certain technologies are going to come into maturity, but it’s more like what the city would look like if we didn’t have cars on the street. So it’s much more about moving with public transport, having lots more greenery and places to live in the street, as well as greater infrastructure for micro-mobility devices, such as bikes and scooters. The way we do this is that we split the city into certain districts, which are each their own traffic Island. This is an engineering traffic concept that’s been taken from other cities around Europe where you create these little mobility zones which are similar to the 15-minute city concept. The idea is that you only move between those traffic islands through more sustainable modes, and things like cars cannot move between them. So you limit the mobility options of cars, so people are more likely to use a more sustainable and active form. So, if that’s the backcasting element, the way we then work with prototyping is we ask ourselves, what does that future mean now? For instance, what happens if we want everyone to travel around with bicycles? What does that mean now?

Because in Copenhagen, even though we already have a rich cycling culture, we experienced cycling congestion. That’s not something that a lot of cities around the world experienced., but we often see there are too many bikes on the bicycle paths. And if we somehow think that we’re going to get even more and more people to cycle, then how is that going to work? Especially when we’re in historic urban contexts, which were built hundreds of years ago, and there is a constrained spatial context. It’s not just simply a matter of widening the street, because we can’t. So to give an example of one prototype that we’ve been developing with the public transport authority “Movia”, which runs the buses here, as well as and the municipality of Frederiksberg, a dynamic streetscape. The idea is that we will embed the street’s asphalt with LEDs and sensors that are connected to public transport, so that we can create a more dynamic street, which gives a better use to space.

That’s the reason why we also talk about Copenhagen because I really would like to show the listeners of my podcast that it has maybe a false image of being the ideal city where everything is working perfectly, and it’s generally heaven on earth. But it’s not like this; you mentioned that bike congestion, and that there are too many bikes. I’ve been thinking as well about cars, that it’s not that Copenhagen is completely car-free. It’s not that there are no cars at all, there are more and more cars to be more precise. And you’ve been doing some projects in Copenhagen. And you mentioned I think, already the dynamic street profile. Could we just say a bit more about it?

I totally can explain it a bit more. As I said that there were LEDs embedded in the road, right. The idea is that because of the way that we currently work with space, in streets, a lot of it is based on physical infrastructure. A bus stop, for instance, is a physical point on the road. It is the same with parking, it’s there all the time, even though it’s only used in demand, right? On Copenhagen streets, there’s often three lanes and then that, so there’s one lane going in either direction. And the middle lane is used as a buffer zone to allow for things like a bus stop so that a car can pass or for parking so that cars can continue. But yeah, as I said, it’s only used like in the case of a bus stop once every 20 minutes, when in some of these constrained streets, the bicycle path is only a meter wide. So when we have a larger form of bicycles, like cargo bikes, which is one of these technologies that we want to see in the streets because they can replace cars. They’re not so adapted to it. So this dynamic street profile that we’re working with takes away that third lane because it creates some dynamism in the street so that we can create a wider bicycle lane, and then that thing like that bus stop can only appear when it’s needed. Does that make sense?

Yes, it makes sense. But I was asking about it because I’ve been to the presentation about this project that you gave some time ago. And you showed it very, very briefly. It was a very short presentation. When I saw it, I was like, huh, is it that easy?

The thing is, it’s not that easy, But this is the purpose of prototyping. it’s simply, how do we try and think about that vision of the future today? I don’t necessarily think that the dynamic street profile is the answer, because there might be problems with pedestrian safety, with the idea that using lights in the street to create a buffer zone for the alighting passengers. We don’t know if that’s going to be safe. But by not doing anything, we’re not going to develop any knowledge and the scale of transformation that we need within the city requires us to think of something big, but we need more knowledge before we’re able to do that. So I think that’s where the prototype of the dynamic street profile comes in.

It’s about prototyping, which I like a lot. And I will maybe explain more later why I’m so interested in this part. But still staying at this topic of prototyping, the ideas, the visions for mobility, I would like to talk about the other project, the other example, which was if I pronounce correctly as to Stureensegade, in one of the districts of Copenhagen, which is called Nørrebro. And there was a very, very big role of prototyping in this project. And it was a time-limited phase of this prototyping before it was or it will be developed further. Could we talk about how those prototyping methods were used there by you and your mobility team?

So firstly, I just need to explain that this project hasn’t gone ahead in Copenhagen or it hasn’t gone ahead yet. But the idea was to transform a residential street in Copenhagen because one of our theses in the mobility department is that when you reduce the reliance on cars and take them away from the built environment, you create spaces of high quality for the people that live there. So our idea was to take away the parking or rather to take away 80% of the parking on the street. So there would still be some parking that could be taken up by like shared cars, but the majority of the road space or the car space would be taken away and this would be transformed into different kinds of amenities. For instance, greater on-street parking,for bikes but also community houses. So places for the residents to come together and cook barbecues or outdoor working spaces, more greenery, because there’s a severe lack of greenery in Copenhagen.

Exactly. That’s just one of the backsides of Copenhagen that I can say strikes me. It’s not a very green city.

Yeah, and they’re having a lot of problems with this because there’s so little green space that when it rains, it floods because it can’t be absorbed into the ground. But back to the street transformation project, the idea would be that in giving up their parking place, and in some sense their car, the residents would each be given a mobility package.

So this mobility package would contain several different services. So you know, it would give them a subscription to the bike share and the cargobike share, also access to a shared car, as well as public transport for the time of the project, which would last about a year. Now, the reason why we were only doing it for a year is first of all, because people are very protective of car parking. I think if you say that you’re going to take anything away, people get very defensive. But when you say that it’s just a trial period for a year, they’re much more accepting. The idea then would be that after that year, we could put the parking back, but still take away, say 10%. So there would be a minor upgrade to the streets. But what would be more hoping is that the residents would pick to keep the improvements and then they could be finalized and made permanent within the street.

How long was this temporary phase of this prototyping?

It was for a year.

So for one year, you remove the cars. And people would get the packages for mobility and different transportation modes. But I’m just wondering, is it enough? What should be the incentive for a person to get rid of a car? Temporary or in a long term.

Yeah, I think we have to talk about mobility. And car use is changing. The number of different technologies that have come out, which could replace cars. We’re gonna go on a bit of a tangent now, but I think people like to call this ‘unbundling the car’. So the way we’ve used cars at the moment is as a vehicle that can do all our journey types.

So it doesn’t matter if we’re going 200 meters down the road to go grocery shopping, or we’re going to drive 1000 kilometres to a different European country, the car is like a vehicle that can service all those trips. But the problem is that you’re paying for a vehicle that isn’t suited to that zero to a 200-meter trip, right?

Financially and environmentally and spatially, and socially, it doesn’t make sense that we use a car to do that trip. I’ll just step back a bit when we look at travel patterns of people, most of the trips that they do are under 10 kilometres. So even though you have this car, which is probably best suited to going a couple of 100 kilometres, you’re mainly using it for shorter trips that it’s not good for. And that’s why we see so much congestion, right? Because everyone’s just using it, one person is sitting in a five-seater car driving under 10 kilometres. But then with the advancements in smartphone technology, which have unlocked the sharing economy, we’re moving from having to own one vehicle to be able to access many vehicles, in the same way that we do now with Spotify or Netflix. We can access an electric scooter, a bike, a cargo bike, a shared car, and we access that when we need it for a certain trip. So to bring that back to the pilot project, it’ll eventually just get too expensive for someone to just own a car that sits outside if they’re not using it appropriately. When we start to take things like environmental impact and the amount of CO2 that causes a release, as when that becomes a tax, for instance, it’s not going to make sense for someone to have it. So we’re going to need to be able to move to these models where we appropriately use transport for what it’s intended to do.

The interesting thing for me is that it’s already quite expensive to have a car in Denmark with a tax of 150% of the value of the car while buying it. Right?

It’s complicated because it’s changing based on the type of car, whether it’s new or old. But yeah, you can say that.

But still, you could say that you have this encouragement for car use or for buying a car. And maybe that could be an incentive on its own. But I think it’s not because we still have so many cars and people can’t afford them. So if they are not distracted by this very, very high tax, it means that they value the use of cars so much that they are willing to pay this extra money and still have a car.

I think cars have become cheaper in the last four years, they’ve reduced a lot of the taxes. So this is why we’ve seen such a big increase in car ownership, especially in Copenhagen. Tied to this is how cheap it is to park on the street. So a parking license. And this changes all the time, or it’s changing at the moment, but I’m pretty sure at the moment, it’s 400 kroner a year for a parking place, which gives you ownership of 15 square meters of public land because you can just park your car for as long as you want.

And it will stay there, it will stay there for 99% of its time or like 23 out of 24 hours of the day.

But I think what’s even crazier is they’ve done studies in Copenhagen and one in every four cars don’t move Monday to Friday. They’re simply a weekend car for people to escape the city. So cars are literally like it’s more than 99% of the time. And the only reason they can do that is that parking is so cheap. We hear anecdotes of rather than hiring storage (like the Pelican storage in Copenhagen) people will simply use their car as an extra room. Because I mean, it’s crazy. Like if you’re renting a room in Copenhagen for 15 square meters, you’re paying 5000 kroner, a month, so yes, you can pay 400 kroner a year, for that same amount of space out on the street, it doesn’t make sense. And this is why I think people are using cars so much.

That’s crazy, because it’s again, it’s similar in other countries and cities. And I can just say something about Warsaw where parking on the street was extremely cheap, it is still but there was a raise recently. And the price I think it was raised for a very like couple of DKK (Danish kroner). And still, it was a huge backlash because people are so used to this extremely cheap occupation of space for their private cars, for the private properties that even you know, when the municipality tried to do something with it, or at least start doing something towards changing the situation. It was like a huge disagreement.

I understand why because for a lot of people a car is essential for them, they can’t get to their job or see their friends without it. So you develop these emotional attachments. and therefore it requires some clever politician to be able to sell the idea of giving up a car. But this is where we see our approach of not trying to take the car away from people but rather provide a better urban environment as our like an addition to the solution to this problem.

I’ve been talking with a very wise polish urbanist once about this similar thing, that a private car is like a private property that occupies the public space, which could be used differently. But this is about this capture of the public space by private property. We were just laughing that if we put the private cars on the street, why can’t I put my sofa outside on the street? Because maybe I don’t have enough space in my flat? So I just want to put the private thing that I’m not using very often somewhere outside my flat. So why can’t I put it on the street?

Yeah, it is crazy. But I think this is what drove the parklet movement in the US. I’m not sure if you’ve seen this where people were renting a car space for a day and then setting up an internet cafe. Like they would just put some fake turf – astroturf on the ground with some chairs and some sofas, and then people would go and hang out. And they would do that once a year as a protest. I think that sparked a whole movement. You can see that now in many cities around the world that parklets as a way of just maybe taking one parking space or two parking spaces and putting in some other amenity are an inroad to getting people to think: Okay, maybe we can use this space for something else than just car storage.

I was thinking about the parklets during our conversation because I think it’s more of a statement than the real change, unfortunately. And this brings me to the explanation of why I was asking about this prototyping so much.

Because back in 2017 there was a Polish foundation called Fix a City Yourself and we had a project that was called “Livable Street” in three different cities in Poland, including the capital city Warsaw. We closed off a street for cars for the weekend and we introduced some temporary street furniture, some benches, some low-cost plants, we even rented them to put it on the street. And we’ve been trying to ask people about this mobility, like: Don’t you feel better now, when you can walk on the street, or when you can bike there? And that later developed into a two or three months long project where we closed off the street every weekend during the summer holidays. And that’s why I think that it was still a statement, not a real change. Because nowadays, this street is again, used for cars only, it was just more of this project, a temporary event that was there for people to maybe try to show them that the street could be used differently, not only for cars. And also, as you said, it’s not about removing the car completely, it’s just giving a good alternative. And that’s why we’ve been making this prototyping project which was an extremely interesting thing to do. It was interesting for me as a young urbanist and designer to have this yellow vest as a street technician, and showing the red lollipop sign, to the car drivers and not allowing them to pass through the street (the residents of the street could pass and reach their houses of course). It was exciting but yet temporary. So I’m just really looking forward to seeing how those projects will move forward from this temporary phase. So coming back to Stureensegade: what was the effect?

I think what you need, and I don’t know your project, so you know, if I’m wrong, just tell me. But I think one of the most important things is recognizing the limits of the agency of the architect and urban planner, like you, actually need to have a strong collaboration with the government and politicians to enact change. So we can demonstrate the benefits. But unless you have that political backing, , that temporary installation is never going to be anything. I will give an example of Times Square in the US that was by Janette Sadik-Khan. She did a similar thing and it was very temporary. She just went out and bought banana lounges and then put them down on Times Square one day to stop traffic. But they had a mayor, I think it was Bloomberg, that said: if you can show me data that this is having a positive effect we’ll just keep the changes. The reaction probably is, as you’re saying, like in your project that people were quite positive about it. But then, because they had that strong political backing, they were able to turn that into a permanent project. And everyone can see how much better than space is now.

I mean, of course, in our case, it was not anarchy and closing the street for cars based on working with the municipality as well. But I think it was even for them, it was more of a temporary project because there’s such a big backlash from the car owners and people starting some small protests. But the bright side of it was that we worked extremely closely with the people living there. So they felt more responsible for the street. And they perceived it in a way “Okay, so I can own a part of a street that I’m living next to”. So I mean, it’s not like a physical owning but like feeling responsible for. And I think that the biggest achievement was that people started to take care of it, they started going out and cleaning their streets (removing the trash or watering the street plants). They started feeling this sense of responsibility. Maybe that’s also how we should act in different places as well? If people start to see that they can be responsible for the street and that parking their private car there for such a long time is not the best idea. Maybe then something will attract them more to change into those, for example, transportation bundles.

I think hopefully, as urban environments become denser and denser, people will appreciate the street a little bit more. Like when space does become a little bit more scarce. We’re going to look: okay, what public land do we own? And that’s going to drive conversations. I think that’s actually what’s driving the conversation right now. Through the Corona pandemic, there’s been a lot of discussion about putting down bike lanes and allowing restaurants to spill out onto the curb and that’s getting people to think: okay, you know, we don’t have so much space, so let’s use it for something that we enjoy rather than just parking a car.

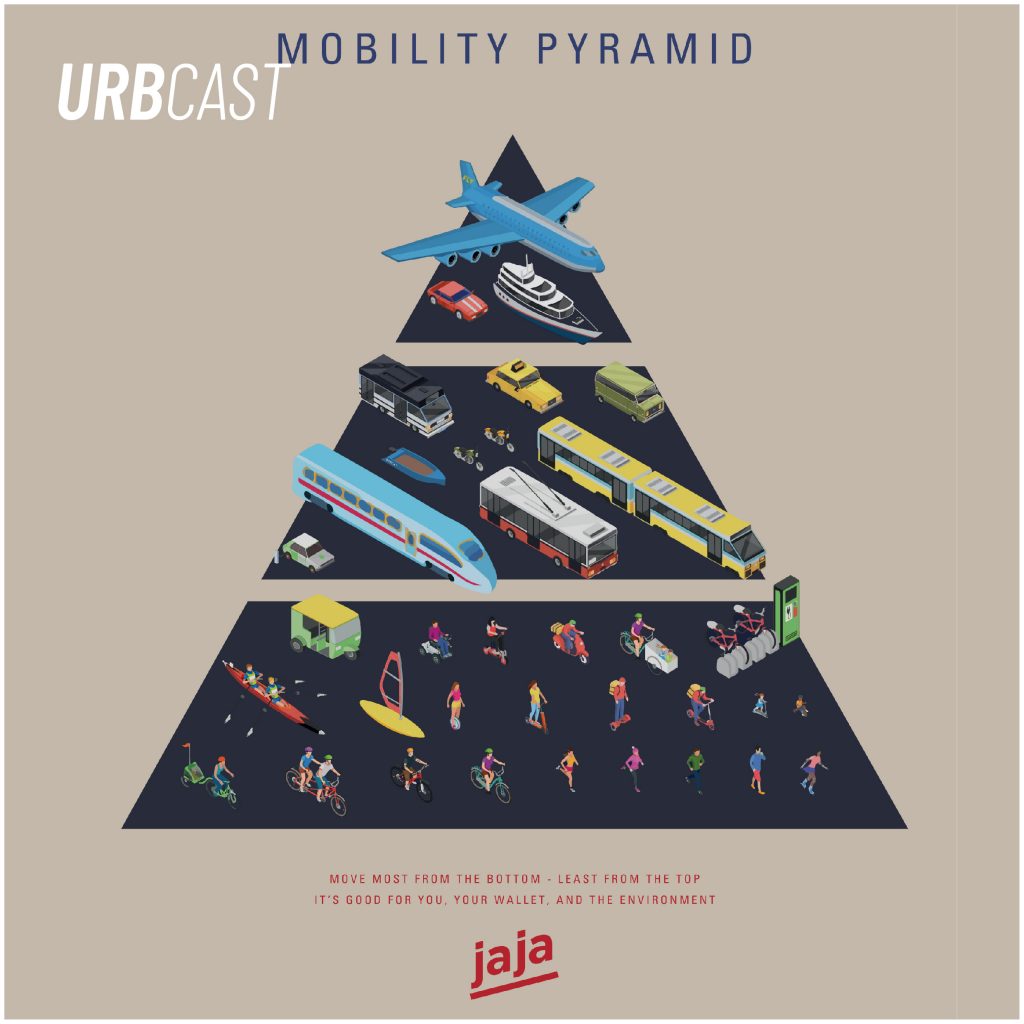

One more thing I wanted to talk about is the Mobility Pyramid that you have been working on for some time. You recently released it to social media and it got quite popular. I saw a lot of people talking about it. And I was just thinking, like, how can we help people understand this pyramid? How could you drive the attention of people to the problem and to this solution that you have in this mobility pyramid? And if you could just explain, what is this mobility pyramid? Is it just a model that could be implemented in other places?

I mean, it’s been quite crazy, I think, it’s been viewed over 50,000 times, it’s been shared over 500 times. It’s taken on a life of its own, which I think is a bit strange as an architect, because I don’t think we’re used to making content that has that reception on social media. So to explain it, I’m not sure whether you know of these diet pyramids, these food pyramids, it’s quite common in Australia. And they have it herein Denmark, too. They just released a new one here in Denmark, which, whereas before, maybe say sugar, and soft drink was at the top, now sugar and soft drink are completely gone, and meat is up there. And I guess it’s a tool for the food industry to try and encourage people to use less meat.

Now, in my work, I’ve been having a lot of trouble, say talking about car freeness. Because I think as we’ve already discussed, cars are very emotional. And when you discuss limiting cars at all, people get very angry.

And so when I’ve been using the word ‘car freeness’, it’s causing unneeded confrontation. Because carefreeness doesn’t necessarily mean a ban on cars, it means a life where you’re free of needing a car. But that is a complicated concept to explain to someone when they’re already angry at you for talking about taking away their car. So we’ve been looking for tools to be able to talk about limiting car use. So this is where taking inspiration from the food industry about reducing eating meat, we thought, what about this is a great idea to reduce people using cars. So the idea is that planes, cars, like boats are on the top, then in the middle, it’s populated by public transport and shared cars and motorbikes. And then at the bottom, you have more active forms of transport, which says, bicycles, scooters, running, rollerblades. And the response has been extremely funny because some people immediately get that analogy, that it’s the food diet and they like it. Other people think it’s some Maslow’s hierarchy pyramid. So they think that the plane is like the absolute best thing. And then, you know, they yell at me. But most of all, I think people automatically think it’s about commuting. So we have a kayak there and they’re like: Oh, that’s so funny, who kayaks to work? We don’t say anywhere that we’re talking about commuting, we just say it’s a mobility period. It’s just like how you should move into your environment. So it’s not necessarily always transporting yourself to work. But the just movement in general.

Thank you, Robert, for explaining it. Because I saw that it was like a lot of reaction on this pyramid and I mean, I think it is how the images work: we aim with them to transfer some vision, but people can perceive it differently.

I guess the main takeaway from it is that we’re trying to think about it as a diet, like everything in moderation that, as I said before, maybe there are times that you need a car, we’re not trying to stop you from going on holiday with your family. We’re just hoping that in the times where it’s more appropriate to use something less impactful on the environment and better for you than we would hope that you do that.

Okay, to conclude it a bit. We started with Copenhagen. And now I would like to ask you about the future of mobility in Copenhagen. I know it’s an extremely broad topic. So let’s just focus on that. Even though there are only 9% of trips taken by car, one single car right takes up to 19 times more space than such a right by public transportation or by bike. And as we said before, cars just, you know, stay still in a garage or on the street for 99% of its time or even more. So what can we do today to reduce car use?

I mean, you’ve hit the nail on the head with a statistic that a car uses, like infinitely more time, more time-space than, than other modes of transport. As for reducing car use, I think it depends on the city, right? So what I suggest here in Copenhagen isn’t necessarily replicable in other cities. It’s going to need a context-driven approach. I would say in Copenhagen, the largest thing that we can do to reduce private car-use is shift to and promote car-sharing models. Like, as we already talked about before, with the weekend, cars, one in four, just sit on the street not being used.

There are different statistics, depending on what study you look at, but they say that a single shared car replaces between 5 and 13 cars.

There’s scope within that, that one in four cars that are used on the weekend could easily shift to a shared car, if not more. So, if you want to talk about the immediate effects that might help way into the future and develop a culture around sharing, I would say we need to look into facilitating better car-sharing systems here in Copenhagen.

So that is the biggest or at least the first step?

We can talk about new lines of public transportation or enabling different types of micro-mobility, more cargo bikes, but I think something that would immediately impact the city is something as simple as car sharing.

Let’s start in one way and take it further from there. I guess we managed to wrap it up and answer the main question of our talk. Thank you very much Robert.

Thank you Marcin, it was a pleasure being here.

If you want to listen to our talk, you can check it here:

38: How can we transition towards car-free cities? (guest: Robert Martin – Head of Mobility at JAJA Architects)